Bach in Japan, por Uwe Siemon-Netto

By Uwe Siemon-Netto

Twenty-five years ago when there was still a Communist East Germany, I interviewed several boys from Leipzig’s Thomanerchor, the choir once led by Johann Sebastian Bach. Many of those children came from atheistic homes. “Is it possible to sing Bach without faith?” I asked them. “Probably not,” they replied, “but we do have faith. Bach has worked as a missionary among all of us.” During a recent journey to Japan I discovered that 250 years after his death Bach is now playing a key role in evangelizing that country, one of the most secularized nations in the developed world.

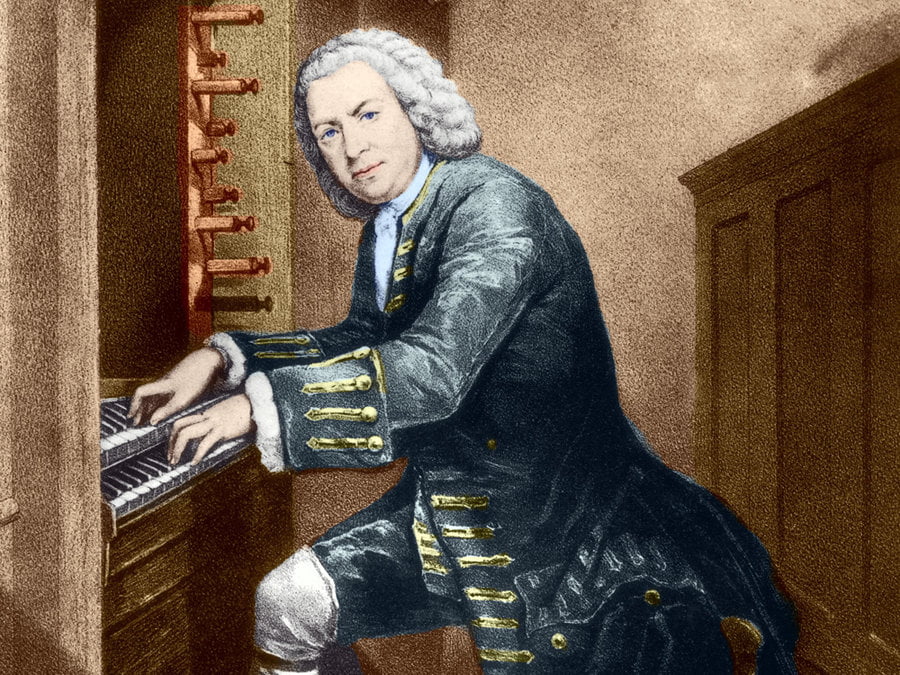

When Bach died on July 28, 1750, after two botched eye operations performed by John Taylor, a quack from England, his last major work, The Art of the Fugue, remained incomplete. It culminates in a quadruple contrapunctus bearing his signature, for it is formed from the letters b-a-c-h (in German musical terminology b-natural is called “h”). Just as you might expect the final section of Fugue 19 to begin, the music stops eerily. The blind man no longer had the strength to pull together its various themes to a perfect ending. Instead he dictated to his son-in-law a powerful last chorale—Vor deinen Thron tret’ ich hiermit (Before thy throne I come herewith)—and then he departed.

The Art of the Fugue is perhaps Bach’s most abstract and intellectually challenging work. Yet its pristine grace led Arthur Peacocke, the English theologian and biologist, to aver that the Holy Spirit himself had written it, using Bach’s hand. A quarter millennium after the composer’s death, this quality of his music provides Christianity with a curious inroad to a group of people who in the past had resisted evangelization more effectively than any other: Japan’s elite.

Masashi Masuda, from Hokkaido, Japan’s northernmost island, told me how Glenn Gould’s interpretation of Bach’s Goldberg Variations had first aroused his interest in Christianity. “There was something about that music that prompted me to probe deeper and deeper into its spiritual origins,” he said. Masuda is now a Jesuit priest and a lecturer in Systematic Theology at Tokyo’s Sophia University. Yoshikazu Tokuzen, rector of Japan’s Lutheran seminary and president of his country’s National Christian Council (NCC), echoed Peacocke: “Bach is a vehicle of the Holy Spirit.” As evidence Tokuzen cited an astonishing statistic. Although less than 1 percent of the 127 million Japanese belong to a Christian denomination, another 8 to 10 percent sympathize with this “foreign” religion. Tokuzen explained: “Most of those sympathizers are part of the elite, and many have had their first contact with Christianity through the music of Johann Sebastian Bach.”

”I fit into this category,” said my interpreter Azusa, a twenty-five-year-old law student. She pulled a CD out of her handbag. It was a recording of Bach’s cantata Vergnügte Ruh’, beliebte Seelenlust, whose lyrics explain that God’s real name is love. “This has taught me what these two words mean to Christians,” she explained, “and I like it so much that I play this record whenever I can.”

Azusa made it clear, though, that while she recognizes Christianity’s beauty as a phenomenon going far beyond cultural aesthetics, she is not yet a convert. In this she typifies perhaps millions of highly educated Japanese who resist taking the leap of faith—or admitting to it—although they are painfully aware of what Tokuzen calls the “spiritual void” into which their society has slipped.

Two-thirds of all Japanese profess no religion. However, of this vast majority, 70 percent deem religion important for society. “Yet Buddhism and Shintoism, Japan’s traditional faiths, have long lost their credibility,” said Martin Repp, a German Lutheran theologian who is the deputy director of the NCC’s Center for the Study of Japanese Religions in Kyoto. “Today their roles are only ceremonial, and most of their temples are mere tourist attractions. Churches could pick up the slack if they were not so self-absorbed, especially the mainline Protestant denominations, to which most Christians in Japan belong,” Repp continued. “Most wealthy congregations are only thinking of themselves and give little money to missions; meanwhile, international mission societies are curtailing their budgets for Japan.” (…)

Seguir leyendo en First Things